The history of St. John of Kronstadt Labor House

- Nikita Sapeguine

- Nov 8, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 19, 2025

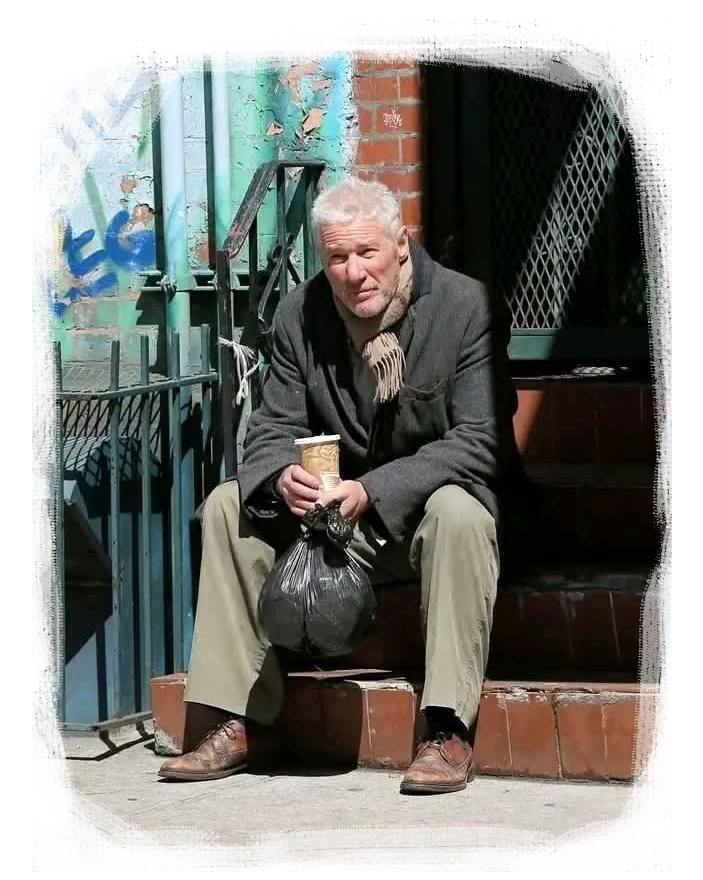

In the second half of the 19th century, there were many poor people in Kronstadt, a port city near the capital of St. Petersburg. Most of them came to work loading ships and could not return home. Father John, being a young priest at the time and at preparing for a Christian mission in Asia, was deeply moved by the sight of Kronstadt poor. Considering all Christians to be one church family, he could not remain indifferent to them, and realized that the flock he was striving to reach is located right here at home. Beginning with private alms, he soon realized that he alone could not cope with the enormous poverty and started looking for like-minded people.

Soon the idea of creating a special shelter, with an emphasis on employment, came to him. Thus was formed the idea of the House of Labor. Let the poor not be beggars and idlers; this is forbidden by Christianity: “He who does not work, let him not eat,” said the strict and merciful Apostle Paul (see: 2Sol.3:10). And Paul himself labored day and night (v. 8). Therefore, everyone should have both shelter and labor: this is where the idea of the House of Labor came from.

For these people, the disposessed citizens of the city of Kronstadt, who lead a miserable wandering life, and had no place to invest themselves in the fall and winter, the Kronstadt church trusteeship established this mission headed by Fr. John.

As Fr. John said, "The arrangement of this house is marvelous, by the grace of God. It begun last spring (1881), with negligible means at first, with God's help and good people..." and became a saving refuge for those in need, and an important milestone in the life of Fr. John, who later in his life gained country-wide notoriety and became known as People's Batjushka (translated as 'priest and fatherly figure').

In 1883, the trusteeship began renting space in a private house from November to April. There were 37 places on bunks for the workers of the newly established hemp-plucking workshop and 15 for everyone else. There was also a lodging house for 110 people, a people's canteen, a reading room and almshouse, a sewing workshop and a junior class of elementary school.

Finally, the trusteeship build its own three-story building for the House of Labour, in 1889.

At first, the canteen of the House of Labor was leased to a private person (a cook), who was obliged under the contract to “give the poor good-quality food for cheap prices determined by the trusteeship”. But it turned out to be unprofitable in 1890, and the trusteeship took over the management of the canteen. The cook became an employee, and a baker was hired. New dishes were brought in, and provisions began to be purchased under the strict supervision of the board members.

For some time the trusteeship supplied the public canteen with vegetables from its cottage, where in summer the orphaned pupils worked under the guidance of an experienced gardener. Private benefactors paid for lunches. In 1890, for example, 9,355 free portions were given out from such earmarked donations. On church holidays the trusteeship paid for the meals.

The incapacitated homeless were given a monthly allowance on the 1st of each month. The parishioners of St. Andrew's Cathedral agreed to put money into a “mug” (a collection box) instead of handing out alms. The money collected was distributed among those who could present a certificate of inability to work issued by a doctor. In different years from 80 to 174 people received monthly payments from the mug collection. Later, one-time allowances were also given: clothes, shoes, funds for treatment, burial, return home, etc.

Inquiries were made about each applicant, in particular, to find out whether he had applied to other charitable organizations at the same time. Up to 3,000 people were under the patronage of the parish trusteeship during the year. The trusteeship provided support to those in need after the fire of 1874, when many townspeople were left without money or shelter. By the beginning of January, a wooden house was erected to which the needy could move in.

In March 1875 in the same house a free elementary public school was opened, which was attended not only by Orthodox children, but also by Lutherans and Jews.

The shoe shop served the needs of the orphan school and provided for free distribution to the poor. The bookbinding workshop, opened in 1884, became a training workshop - the master received a room for work, and instead of rent he took boys of 10-15 years old for training.

The basic work of the House of Labor male residents was hemp-plucking and cartouche workshops (where boxes and paper bags were glued) for men. Although the labor was hard and the possible earnings were low, it allowed the needy not to starve to death. In the hemp-plucking workshop, old ship's ropes were shredded into fibers from which new twines, ropes, hammocks and nets were woven.

Over time, 60-100 people worked daily in men's and women's workshops, and their products - shoes, clothes, furniture, tablecloths and napkins, and household items - were in demand at bazaars and shops. Since it turned out that the qualifications of most of the women who came did not meet the needs, very soon sewing and needlework courses were opened at the House of Labor.

Over time, a free public school for 200 people with classes for different literacy levels was opened at the House of Labor, and lectures on religious, historical and literary topics were held. Then there was a library with 3,000 volumes, a free reading room and a paid library. A bookstore with literature for children and adults was opened.

On November 2, 1909, a school of craft apprentices was opened in the House of Labor in Kronstadt. Initially 30 pupils were trained in the locksmith department and 8 in the carpentry department.

On October 18, 1912 the school of applied crafts was opened. The first floor housed the workshops of the junior locksmith class, a blacksmith's workshop and a workshop for the study of electrical work. On the second floor there were lathe, locksmith and carpenter workshops and classrooms. In 1922 it housed a school of factory apprenticeship, which under different names but with the same number and profile of activity exists to this day.

The House of Labor in Kronstadt was not self-supporting and existed mainly on donations. For example, only the personal contributions of Fr. John's personal contributions to the House annually amounted to about 40 (according to other data - 50-60) thousand rubles, which came to him from about 80 thousand annual pilgrims. During the 20 years of the House's existence, he contributed more than 700 thousand rubles to its needs.

Although the revolution put an end to the House of Labour, St John’s endeavour didn’t go in vain and became an inspiration for God-loving Christians and enthusiasts who established similar homeless shelters.

We believe it is now our turn to continue St John’s labour of love in the 21st century Brooklyn. Among the hurdles and obstacles, we continue to witness God’s blessings and amazing cases of answered prayers (link), encouraging us to carry St John’s legacy!

Source of historical information: https://opora-sozidanie.ru/?p=13834

Comments